Prado and collaborators published “Supporting children to grow smarter, not just taller: here’s how” in Early Childhood Matters. Read the article at the Early Childhood Matters website.

Author: jovo

Going to the 2020 Micronutrient Forum? Check out these presentations from the TRELLIS lab:

ON-DEMAND

.png)

Thursday, November 12, 2020

1:30 PM – 3:00 PM EST

Friday, November 20, 2020

11:00 AM – 12:00 PM EST

Ten Steps to Success for Measuring Early Childhood Development in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

![]()

A paper just published in the Journal of Nutrition reports the first study to use automated eye tracking to measure infant developmental outcomes of a nutrition randomized trial. Effects of early nutrition on infant neurobehavioral development are typically measured using assessment of behavioral milestones, such as crawling and saying words. These assessments may not be highly sensitive to individual differences between children because there is a wide range of variability in the age children attain these milestones that is normal. Children’s scores on these types of measures during the first two years after birth are not strongly correlated with children’s later cognitive abilities.

![]()

Measures of infant looking behavior may be more sensitive than measures based on milestone attainment. Infants’ eye gazes provide meaningful information about their cognitive processing. For example, an infant’s novelty preference, demonstrated by looking longer at a new picture compared to a previously seen picture, shows that the infant remembers the previously seen picture. Automated eye trackers detect the gaze focal point using an infrared light source and a set of cameras that capture the light reflected from the cornea. Recent advances have made this technology more feasible for use in low- and middle-income country settings. In this study, we used automated eye tracking to assess infant cognition in Malawi, in combination with commonly-used developmental assessments based on acquisition of behavioral milestones.

![]()

The trial was designed to test whether feeding children eggs during the complementary feeding period improves growth and development and was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The trial was led by Dr. Christine Stewart at the UC Davis Institute for Global Nutrition and Dr. Kenneth Maleta at the University of Malawi College of Medicine, with the developmental outcomes led by Dr. Elizabeth Prado at the UC Davis Institute for Global Nutrition in collaboration with Dr. Lisa Oakes at the UC Davis Center for Mind and Brain.

Eggs are nutrient-rich foods, which have been found to promote child growth in Ecuador. We enrolled 660 children age 6-9 months in rural Malawi and randomly assigned half of the children to the intervention group, who received seven eggs per week for the study child and seven eggs per week for the household, and half of the children to the control group, who did not receive eggs. After six months, we did not find any differences between the group who received eggs and the control group in attention, memory, language, motor, or personal-social skills, except a smaller percentage of children who received eggs had delayed fine motor skills, such as picking up small objects with their fingers. This study highlights that positive effects of egg interventions may be found in some contexts but not others, which should be considered when deciding whether to invest in programs to promote child egg consumption. Although we did not find effects of the intervention on the eye-tracking measures, we successfully obtained usable data from 60% of targeted children at age 6-9 months and 72% of targeted children at age 12-15 months. These success rates were obtained in the context of a full day of data collection and project activities for the participants, with as many as 25 participants assessed on any given day. This suggests that automated eye tracking is a new promising method to evaluate early child development in nutrition research in low- and middle-income countries.

On February 27, 2020, Dr. Elizabeth Prado and Dr. Seth Adu-Afarwuah launched a new project in Ghana funded by $2,600,000 from the US National Institutes of Health. The project will be the first long-term follow-up in Africa of a randomized controlled trial in which the intervention group received a fortified food during most of the first 1000 days, from early pregnancy through 18 months of age.

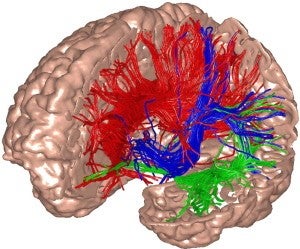

Nutrients such as vitamins, minerals, and fatty acids are the building blocks for children’s healthy brain development. Much of the brain’s structure is laid during pregnancy and early childhood, when the brain and nervous system are developing very rapidly. Many pregnant women and young children do not eat sufficient nutrient-dense foods that contain these essential nutrients. If these nutrients are not available during critical periods when the brain is developing rapidly, there could be long-term effects on the structure and function of the brain and nervous system.

This new project will follow up children at 8-12 years of age whose mothers participated in a randomized controlled trial of nutritional supplementation when they were pregnant 10 years ago. The  original trial, the International Lipid-Based Nutrient Supplements (iLiNS) DYAD (mother-child dyad) trial, was led by Dr. Kay Dewey at UC Davis and Dr. Anna Lartey at the University of Ghana and was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Pregnant women and children in the intervention group received lipid-based nutrient supplements (LNS), made from peanut paste, vegetable oil, and milk powder, with added vitamins and minerals. While small-quantity LNS provides only a small amount of calories per day (~118 kcal), it is packed with the vitamins, minerals, and fatty acids that are needed for children’s growth and development. In the control groups, women received a daily micronutrient capsule, similar to a pre-natal multi-vitamin, and the children did not receive any supplement.

original trial, the International Lipid-Based Nutrient Supplements (iLiNS) DYAD (mother-child dyad) trial, was led by Dr. Kay Dewey at UC Davis and Dr. Anna Lartey at the University of Ghana and was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Pregnant women and children in the intervention group received lipid-based nutrient supplements (LNS), made from peanut paste, vegetable oil, and milk powder, with added vitamins and minerals. While small-quantity LNS provides only a small amount of calories per day (~118 kcal), it is packed with the vitamins, minerals, and fatty acids that are needed for children’s growth and development. In the control groups, women received a daily micronutrient capsule, similar to a pre-natal multi-vitamin, and the children did not receive any supplement.

When the children were 4-6 years of age, we found that children in the LNS group had fewer social-emotional difficulties compared to the control groups, especially those from home environments with low nurturing care and learning opportunities. The aims of the new project are to see whether we find the same pattern when the children are 8-12 years of age and to understand the neural mechanisms of protective effects of early nutrition on the development of social-emotional difficulties among children in Ghana. This will be the first randomized controlled trial to assess long-term  effects of early nutritional supplementation on nervous system development through combining methods to assess neurophysiology in both the central and autonomic nervous systems, including structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and measures of autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity, including electrocardiogram and impedance cardiography. Co-investigators are Dr. Paul Hastings and Dr. Amanda Guyer at UC Davis, Dr. Adom Manu and Dr. Benjamin Amponsah at the University of Ghana, and Dr. Brietta Oaks at the University of Rhode Island.

effects of early nutritional supplementation on nervous system development through combining methods to assess neurophysiology in both the central and autonomic nervous systems, including structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and measures of autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity, including electrocardiogram and impedance cardiography. Co-investigators are Dr. Paul Hastings and Dr. Amanda Guyer at UC Davis, Dr. Adom Manu and Dr. Benjamin Amponsah at the University of Ghana, and Dr. Brietta Oaks at the University of Rhode Island.

Study Looks at Preventing Stunted Brains, Not Just Stunted Growth

A new study led by researchers at the University of California, Davis, shows that caregiving programs are five times more effective than nutrition programs in supporting smarter, not just taller, children in low- and middle-income countries.

The research, published in the journal The Lancet Global Health, examined 75 early intervention programs and their effects on children’s growth and brain development. Researchers have known adequate nutrition during pregnancy and childhood improve both conditions. But children growing up in poverty face a variety of risk factors that could govern growth and development differently.

“Our study found that we can’t just focus on nutrition. Other aspects of nurturing care are just as, if not more important in supporting healthy brains,” said lead author Elizabeth Prado, assistant professor of nutrition at UC Davis.

Prado says interventions that promote caregiving and learning, such as parents playing games, singing songs and telling stories with their children, have far bigger effects on children’s cognitive skills, language skills and motor development.

“We knew that nurturing care was important but were struck by how big its benefits were compared to nutrition and growth,” added Leila Larson, a lead collaborator from the University of Melbourne.

Investing in caregiving and learning

Global health programs typically focus on preventing stunting, when children are not growing in height the way they should for their age. Stunted growth has also been associated with lower than average school achievement and cognitive scores.

“The association has been influential in prioritizing a global agenda to promote nutrition and growth,” said senior author Anuraj Shankar, with the Center for Tropical Medicine and Global Health at Oxford University. “However, our true goal isn’t just for children to grow taller but for them to fulfill their developmental potential. The study shows that won’t happen unless we target caregiving to nurture thriving individuals and communities.”

Globally, an estimated 156 million children younger than 5 years have stunted growth and an estimated 250 million are at risk of not fulfilling their developmental potential.

Media contact(s)

Elizabeth Prado, UC Davis Department of Nutrition, 301-697-9542, elprado@ucdavis.edu

Amy Quinton, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-752-9843, cell 530-601-8077, amquinton@ucdavis.edu

Karen Nikos-Rose, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-219-5472, kmnikos@ucdavis.edu

Anuraj Shankar, Center for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Oxford University, 617-955-6724, anuraj.shankar@ndm.ox.ac.uk